Putting together a good back workout for mass can be a considerable challenge.

There are so many ideas, anecdotes, and tricks that picking out the useful information can feel nearly impossible.

To that end, I’ve put together this guide for you. So, if you’re interested in:

- Back anatomy and function

- The best back exercises for mass

- Optimal training volume and frequency

You’ll absolutely love this guide. Let’s dive into it.

More...

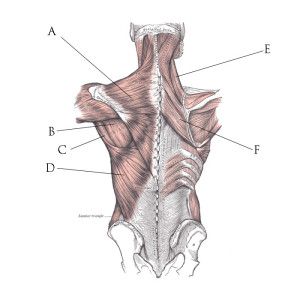

But First, We Need to Understand the Back Muscles Anatomy

Your back muscle group is the biggest and most complex, training-wise, in your entire body. There are a lot of muscles that work together but the four main ones we are focusing on are:

A is Trapezius

D is Latissimus dorsi

F are the Rhomboid major & minor muscles

The Erector spinae aren’t shown in the above chart but they lie in the lower grey area of the back.

There are also a few smaller muscles pointed out in the above chart:

B is the infraspinatus

C is the teres major

And here is what a developed back looks:

This is Martin Berkhan, the creator of www.leangains.com

One of the best sources on intermittent fasting online.

His approach to training and nutrition is simple: lift heavy ass weight and fast for 16 hours a day. Highly recommend his work.

And this is Mike Matthews, the creator of www.muscleforlife.com

There are tons of incredibly well-written and researched articles on everything you need to know on building a solid physique.

His books have helped thousands of people transform their bodies and there are tons of success stories on his site.

And for you girls:

Sure, they don’t look as impressive next to some of the roided out bodybuilders and physique competitors, but this is what you can aspire to get if you are a natural lifter.

Evenly developed, good proportions, width, thickness and strength.

Where Most People Go Wrong With Their Back Workout For Mass

Back training is complex. A lot of people train theirs incorrectly and can’t make good progress for months, even years.

Usually, people fall into one of two categories:

They try to inflate their ego by pulling heavy weights that don’t do much for them;

or:

Focus on cookie-cutter programs that use gimmicks and ineffective strategies.

In both cases, the results are pretty much the same:

Back so flat that gets pancakes jealous.

And since building a solid back is our goal, the first thing we need to do is check the ego at the door. Ego lifting is ugly, unproductive and even dangerous. Especially true for the back where mind-muscle connection plays a huge role.

And if ego lifting is not your problem and you’re in the other category, you need to stop wasting time following dumbass programs designed to keep grandma and grandpa in shape.

What you need is to learn what the most effective back exercises are, how to build your routine, how to progressively overload your back, and what mistakes to avoid. We’ll cover all that below.

The Best Back Exercises for Mass and Strength

Let’s lay down the fundamental part of training first: exercises. There are hundreds of them, but only a few we’ll go over.

The Deadlift

The deadlift is one of the best exercises that develops the entire body, including the back. It works a range of muscles, improves grip strength, and is a very safe movement.

Some people consider it to be a very dangerous exercise, but that’s not true. As long as you do it with caution and avoid doing high repetition touch and go sets, you shouldn't ever have problems with the lift.

If you do have a history of back issues and injuries, you might want to steer clear from heavy compound lifts for more isolation work.

Let’s take a look at the five most widely used deadlift variations:

1. Conventional Deadlift

The deadlift is probably the most famous of all exercises, and it is great for developing not only your back but also your hamstrings, glutes, calves, quads, core and grip strength.

Here is a great in-depth video by Alan Thrall. He goes over form, mental tricks to perform better and common mistakes.

2. Sumo Deadlift

The second most popular deadlift variation, and it’s gained quite a bit of popularity in the last two decades. One of the reasons for that is because this is a great alternative for the conventional deadlift. Some people are better built to deadlift in a sumo style and find it much more comfortable than the conventional deadlift.

You can read more about it in this article by Greg Nuckols. And here is an instructional video on how to perform the sumo deadlift.

3. Rack Pull Deadlift

This variation has you pull the bar from an elevated position and essentially eliminates the initial part of the deadlift. While this variation might seem like cheating to some of you, it’s awesome for two things.

- If you’re having trouble locking out the bar at the top, rack pulls can improve your lockout strength.

- Rack pulls drastically reduce the involvement of your legs in the lift and instead put the biggest emphasis on your hips and back, making rack pulls an amazing exercise to overload your back.

4. Deficit Pull Deadlift

The deficit deadlift, unlike the rack pull, emphasises the initial part of the movement to help you build more strength off the bottom. If you’re having trouble breaking the weight off the floor, but the lockout is no problem, then using this variation is a great way to fix that problem.

5. Trap Bar Deadlift

Unlike the barbell version, with this one, you stand inside and grab the handles on each side. It allows you to use a neutral grip for the lift and most people can pull a bit more weight compared to the barbell version.

You can learn more about the trap bar deadlift in this post. Also, here is a video demonstration.

The Most Frequently Asked Questions About the Deadlift

The Pull-up and Chin-up

Pull-ups are a great exercise to develop a strong back, and they say much about your fitness level. A lot of guys feel intimidated by them; others feel ashamed because they cannot do them, so they throw them out the window.

But, learning how to perform them is one of the best things you can do for yourself. They will strengthen and develop your back, and once they get easy, you can always attach a weight belt on yourself to keep progressing.

The chin-up is a very similar exercise to the pull-up, but with one big difference: hand position. On the chin-up, your hands are supinated, allowing for more bicep involvement and activation.

Both the chin-up and the pull-up target your back and bicep. The chin-ups have more bicep activation, whereas the pull-up targets your back a bit more.

Pull-up Progression (Even if You Can’t do a Single Repetition Yet)

I’m kind of ashamed to admit that for the longest time, I couldn’t do a single pull-up. And it’s not because the movement is that difficult to master, but because I didn’t bother to learn.

And when you can’t do even a single repetition, it can be discouraging. I get it.

But mastering the pull-up is not hard. It requires some time and the right tactics, so let’s review:

1. Band or Partner-assisted Pull-ups

The goal here is to help you overcome your lack of strength to a degree and help you learn how to properly execute the pull-up.

2. Negative Pull-ups

The eccentric contraction is a powerful tool you should use to gain strength and muscle mass. And with the pull-up, it’s no different. If you can’t pull your body weight through a full range of motion, you can at least focus on the negative part of the lift, and build your way up to the first repetition.

The goal is to get yourself to the top position of the pull-up by using a chair, box or jumping and then fighting gravity on the way down and lowering yourself as slowly as you can.

I could finally do my first pull up around the time I started holding a negative for about 45-50 second.

Word of warning, though: If you haven’t tried this before, get ready to experience the greatest lat activation and burn you’ve ever felt.

Daniel Vadnal from www.fitnessfaqs.tv demonstrates how to do them perfectly.

3. Inverted Rows

The inverted row mimics a pull-up, and with it, you can adjust the angle of your body to your strength level on the pull-up.

A great place to do these is on the smith machine.

4. Lose some weight, if you must

A no-brainer, but many people overlook it. You’d have a much easier time learning how to do pull-ups if you were a few pounds lighter. If you lose 10 pounds of fat and maintain your muscle mass, you’ll learn how to do pull-ups much faster.

Check out my guides on training and eating for fat loss (and my take on motivation).

These are the four tactics I’ve used to build up my way to my first pull-up. On their own, they are effective, but together, they’ll get you there much faster.

Your Action Plan for Your First Pull-up

I recommend adding 3-4 sets of inverted rows in the middle of one of your workouts. Adjust the height to allow you to do 8-10 repetitions with good form.

Add 3-4 sets of negative pull-ups in the middle of another workout. For example, after your heavy work on leg day, do 3-4 sets of negative pull-ups. You can also superset them with the accessory movements for your legs.

And remember: the goal is to lower yourself down as slowly as you can. The number of repetitions doesn’t matter.

And finally, add 3-4 sets of band or partner assisted pull-ups as one of your exercises on your back day, as first or second, while you’re still fresh and strong. Don’t hit failure on any of the sets, only on the last set if you wish. The goal is to build up volume through repetition.

You won’t do much good for yourself if you go all in on the first set and you can only do 3-4 band-assisted pull-ups on the following sets.

The high frequency and moderate volume are going to help you build up the back strength and learn how to perform the pull-up faster. And if you’re somewhat (or very) overweight, losing some excess fluff is going to speed up the process.

Onward to your first pull-up!

The Barbell & Penlay Rows

Barbell and Pendlay rows are two great exercises for back development.

The main difference between the two movements?

With the barbell row, your goal is to keep your torso as parallel to the ground as possible without letting the bar touch it.

With the pendlay row, you get to set the bar down between each rep, which reduces the involvement of your core as a torso stabilizer.

Neither of the two variations is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ and whichever you decide to do is up to you. Keep in mind that barbell rows often turn into ego rows. What happens is guys load up much more weight than they should and keep their torso very upright. And what happens is they shorten the range of motion a lot and end up doing some shrug rather than a row.

With pendlay rows, it’s much harder to ego row because you’re pulling the bar off the floor for each rep and your torso is parallel to the floor.

Here is a video on how to perform barbell rows.

And here is a video on how to perform pendlay rows.

5 Effective Accessory Back Movements

Now that we’ve gone over the most important exercises for a solid back, it’s time to take a look at some of the accessory movements you can do to put the finishing touches to your routine.

1. T-Bar Rows

Now we’re getting into the meat and potatoes. Knowing how much volume and how often to train is just as important as the above points.

To those unfamiliar with the term ‘training volume,’ it refers to the amount of work you do within a given workout. Your best option is to count the number of working sets you do per workout.

While people have multiple opinions on what makes for a good back workout for mass, you should aim to do less rather than more while still making good progress.

Let me explain myself:

For your training to stimulate muscle growth, you need to disrupt homoeostasis. A straight-forward process, but many people don’t get it.

You’ve got your action (training), and your body produces a reaction (adaptation and growth).

What you need to do is learn what the optimal amount of volume is for you. That way, as you progress, get bigger and stronger, and the ‘optimal volume’ no longer produces results (due to the repeated bout effect), you have more room to add work.

If you can make sustainable progress doing 12-14 sets for your back and your strength increases (provided you nutrition and recovery are in check), keep at it.

As you get stronger and start doing more weight on each exercise, the total volume done for each workout is going to increase even if you don’t add more working sets.

And once your gains start to diminish and you see yourself hitting a plateau in your training, you then have room to add in more work.

(By adding more working sets or workouts within a given week).

The bottom line?

Training is about causing enough damage to which your body can positively respond.

So where do you begin?

What I recommend if you’re an intermediate lifter (with more than 6-8 months of lifting experience):

Start off with 12 to 14 working sets for your large muscle groups (back, chest and legs). See how your body responds, provided your nutrition and recovery are in check.

If you can make good progress with that many sets, don’t add more work for the sake of adding more.

But, if you feel like you’re plateauing, adding more work (within the same workout, or another day of the week) is something you need to consider.

Training Frequency and the Norwegian Experiment

Training frequency measures how often you train a given muscle group (e.g., your back) or, if you’re more strength-oriented, a lift (e.g., the deadlift).

There are lots of opinions out there, but few are backed by any facts.

In this article written by Martijn Koevoets, a very interesting study is showcased - the Norwegian experiment. In the study, the Norwegian school of sports sciences set out to examine the effects of high-frequency training when compared to a low-frequency protocol.

What’s great about this study is that the subjects were all highly trained, and the common response of some people, “Those are just newbie gains!”, doesn’t apply.

Each of the participants had trained for competitive powerlifting for at least one year. All of them also competed in the national Norwegian IPF powerlifting competitions within the previous six months.

There were 16 participants between the ages of 18 and 25. Thirteen were men and three were women. They were pretty strong, too:

Their coach, Dietmar Wolf, set up the 15-week training program with the same exercises, training volume, and intensity for everyone. The 16 participants were split into two groups:

One group had three training sessions per week and the other group trained six days a week. For the volume to be equated, the low-frequency group had to do twice as much work in each workout when compared to the 6-day group.

After 15 weeks, the results were interesting:

The high-frequency group increased their squat and bench press nearly twice as much when compared to the low-frequency group (11±6% vs. 5±3% and 11±4% vs. 6±3%, respectively).

There were no significant differences in strength gains for the deadlift (9±6% vs. 4±6%).

The researchers also looked at changes in muscle mass for the vastus lateralis and quadriceps as a whole. The average increase for the high-frequency group was nearly 10% in the vastus lateralis and 5% in the quad as a whole.

On the other hand, the low-frequency group didn’t experience any significant hypertrophy.

This study, though it never got published in any peer-reviewed journal, led many people to believe that more frequent training = more gainz. And while this may very well be the case for strength improvements, it’s not as simple for muscle growth.

In a recent meta-analysis, Brad Schoenfeld and colleagues concluded that, as long as training volume is equated, training more frequently doesn’t lead to faster progress in the gym.

Still, there’s one caveat:

Sure, training volume is the main driver for muscle growth, and more is better, to a point, but training frequency is a valuable tool we need to take advantage of due to volume allocation.

Say, for example, that you are currently doing 16 sets for your back each week, all crammed into one workout. Once you’re done with the first half, you’re probably feeling fatigued which means you either need to reduce the weight you are lifting or do fewer repetitions.

Now, if you were to split these 16 sets across two training sessions, you would train your back more effectively because you would have some recovery time (2-4 days) between the first and second half. This would allow you to use more weight on each set, maintain good form, and do more repetitions.

Over time, that would lead to more progress. So, my recommendation for training frequency is this:

If your schedule allows you, train your back across two or three sessions, instead of cramming all sets into one workout. But remember - the total sets should stay roughly the same (around sixteen). You don’t want to pile on more and more work for your back, just because you can.

Progression and Growth

I won’t dwell much on this point, but it needs to be said: if you want to develop a solid back, you need to improve your performance over time. No matter how often you train your back, what exercises you choose, and how much you eat, the single most reliable way to force growth is to do more.

If this week you hit 315 pounds for 5 sets of 3 reps on the deadlift, aim to see improvements in the weeks again: whether you add more weight to the bar (of course, while doing the same number of sets and reps), lift the same weight with smoother form and more speed, or even the same weight for more repetitions.

You need to improve over time. But since you can’t improve what you don’t track, I recommend using a workout journal/simple notebook or a phone app (I use and adore Evernote) to write down your numbers each week. That way, you’ll have a much better understanding of your progress.

Always keep The Repeated Bout Effect in mind:

If nothing changes, nothing is going to change.

Read next:

Leave a Reply