If you've ever asked yourself, "How many sets should I do per workout?" this guide is for you.

Today, we’ll go over things like:

- What sets and reps are

- What your workouts should achieve

- How many sets and reps you should do

And much more.

So, without further ado, let’s dive in.

More...

What Are Sets And Reps?

Before getting into the meat and potatoes of this guide, I'd first like to clear a few things up, so we are on the same page.

In the context of weight training, sets and reps are what make up our workouts. Rep, short for repetition, is a single complete motion on a particular exercise. For instance, if you hold a dumbbell in one arm, curl it, and lower it, that's an example of one repetition.

A set is a collection of repetitions you do consecutively before taking a break. For example, if you grab that same dumbbell, curl it, lower it, repeat ten more times, and set it down, that's an example of a set.

Rep by rep, we create sets, and set by set, we create workouts. It's so simple, yet so complex. Let's break it down further:

What Should The Goal Of Your Workouts Be?

Before getting into specific recommendations on sets and reps, it's good to have a basic idea of what our workouts should achieve. Regardless of what your specific goals are, a good workout is one that:

- Causes a significant enough disruption

- Triggers positive adaptations toward our goals (muscle growth, strength gain, etc.)

Of course, this is simple to understand but difficult to apply successfully. Why? Because we are all different, and no single workout will disrupt the body and trigger improvements in the same way for everyone. For instance, one person might need a couple of sets to get a pump, feel sore, and make progress. Another person might need to do a dozen sets to cause even half the disruption—context matters.

But what does disruption mean, anyway? Well, for general strength and muscle growth, it means you should:

- Get some sort of a pump

- Feel the correct muscles working and getting tired

- Experience some degree of soreness in the following days

Having a pump is not always vital. For instance, you likely won't experience much of a pump when lifting heavy weights for fewer reps to get stronger. Muscle soreness also doesn't signify an effective workout or predict future progress. It only means that you've stressed your muscles to some degree.

And while not essential, these factors can tell us a lot about the amount of work and effort we are putting into our workouts. For instance, if you never feel a pump or rarely get any soreness (even when trying new things), it could be a sign that you're not training effectively.

With that said, how well you're progressing toward your goals is also vital. For example, if you rarely feel soreness or a pump, but you're making good progress, who am I to say you're not training effectively?

Determining the effectiveness of your training comes down to a few things, and you will get better at estimating it as you build experience. Plus, you should never chase a pump or muscle soreness for the sake of it. Doing too much work can have the opposite effect and push you away from your goal, rather than pulling you toward it (1).

If your workouts are so difficult that you can't recover in time or you feel sore all the time, consider doing less for a while to see how that impacts you.

More Work Equals Better Gains, But Is This The Whole Story?

Doing more work delivers better results, and we have several good studies that back this idea up. For instance, a meta-analysis by James Krieger found a linear relationship between the number of sets we do and the growth we experience (2). Doing four to six sets instead of one can results in up to 90 percent more growth.

A more recent meta-analysis by Schoenfeld and colleagues had similar findings (3). When comparing 1-4, 5-9, and 10+ weekly sets per muscle group, more volume leads to linear increases in muscle growth.

You can see why so many people today fixate on the high-volume approach.

The problem is, volume alone should not be our only consideration. While important, this is one piece of the puzzle, but there are others. For instance, we also need to consider how the training we do now will impact the remainder of our workout and training week. If we get too tired and can't train hard later, did we do better?

Sure, training should cause fatigue. But when we examine it further, the answer isn't as simple as, "Do more to grow more."

Number of Sets Per Workout: Is There An Upper Limit?

As we discussed above, the goal of our workouts should be to cause a significant enough disruption and trigger positive adaptations. So, there exists a theoretical point of "just enough." The problem is, going beyond it can have the opposite effect. Instead of growing more from the extra work we do, we only get more fatigued and achieve the opposite.

Of course, this theoretical point is different for everyone and depends on factors like:

- Experience - how used your body is to training stress.

- Age - the younger you are, the easier it is for you to recover (4).

- The exercises you do - some movements are more fatiguing.

- How hard you push yourself (1).

- How well you're sleeping (5).

- What your nutrition is like - your diet’s quality and the number of calories you’re eating.

- How stressed you are outside the gym.

For the question, “How many sets should I do?” no single answer applies to everyone. One person might do well with five sets per muscle group per workout, where another might need twice that. Let's take two people as an example here. The first one is John - a forty-something father of three with a full-time job. The second is a twenty-year-old college student who doesn't have a family or full-time job yet. His name is Steven.

At first glance, John and Steven might do well with similar training programs. But when you think about it, that makes absolutely no sense. Steven is younger and less stressed. John is older and has to deal with fair amounts of stress. So, Steven should be able to do a lot more work and still recover well. On the other hand, John needs to be careful.

So, what I recommend is to experiment with what works well for you. Start with less work, gradually add sets over the weeks, and notice when you start running into recovery issues. Specifically, look for symptoms like:

- Unusually pronounced muscle soreness

- Weakness and inability to recover well between workouts

Once you've reached that point, drop the volume to a degree and go from there.

What Does This Mean In a Practical Sense?

We know that studies recommend 10 to 20 weekly sets per muscle group for optimal muscle growth. We also know that training volume, independent of training frequency, is the biggest predictor of muscle growth (6).

So, I recommend starting with around ten weekly sets for your larger muscles (chest, back, and quads) and about five weekly sets for the smaller ones (biceps, triceps, shoulders, etc.).

Now, the question of "How many sets should I do per workout?" will come down to your weekly training frequency. I typically recommend a frequency of twice per week for each muscle group because that allows for better volume allocation. Instead of cramming all of the work inside a single workout, you can spread it out a bit. This lets you do your sets in a fresher state and work harder.

For example, if you start with ten sets per week for your chest and split it into two sessions, it can look like this:

Monday - 5 sets

Thursday - 5 sets

You can bump that volume gradually over the weeks:

Week 2:

Monday - 6 sets

Thursday - 5 sets

Week 3:

Monday - 6 sets

Thursday - 6 sets

Monitor your recovery and progress, and adjust. In doing so, you avoid doing too much at once and get to do all of your sets in a fresher state.

You can use this rule to program your training quite simply. Say, for instance, you decide to do the following amount of work per muscle groups as a start:

Chest - 10 sets/week

Back - 10 sets/week

Quads - 10 sets/ week

Shoulders - 5 sets/week

Triceps - 5 sets/week

Biceps - 5 sets/week

Hamstrings - 5 sets/week

Calves - 5 sets/week

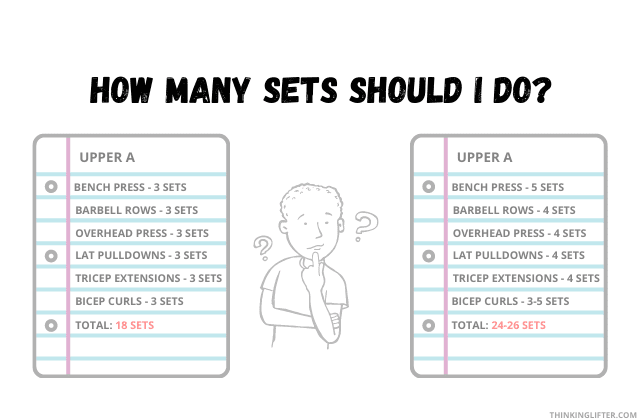

You can split that volume into four workouts. For example, here is how it might look with an upper/lower split:

Upper 1:

Chest | 5 sets |

Back | 5 sets |

Shoulders | 3 sets |

Triceps | 2 sets |

Biceps | 3 sets |

Lower 1:

Quads | 5 sets |

Hamstrings | 3 sets |

Calves | 3 sets |

Upper 2:

Back | 5 sets |

Chest | 5 sets |

Shoulders | 2 sets |

Triceps | 3 sets |

Biceps | 2 sets |

Lower 2:

Quads | 5 sets |

Hamstrings | 2 sets |

Calves | 2 sets |

Before we move on, you might be wondering why I recommend fewer sets for smaller muscle groups. One reason has to do with overlap. Since the smaller muscles like your biceps and triceps work with the larger ones like your back and chest, you don't need that much direct work to grow them.

For example, if you do ten sets of back work for the week, your biceps work the entire time, so you get ten sets worth of indirect stimulus. Then, with an extra few sets of direct work, you can optimize their growth.

But How Many Sets Should I Do If I Train For Strength?

What we've covered so far primarily applies to hypertrophy training, but it also applies to strength gains to some degree. Still, there are a few differences to be mindful of.

First, you can get away with a bit less training volume and still build a lot of strength. Where studies show that 10 to 20 sets per week build muscle optimally, we can get quite strong with as few as 8 weekly sets.

Second, while you can build muscle well with a frequency of once per week, strength benefits from a higher frequency. Like many things, lifting weights is also a skill that improves through repetition. For instance, if you were given three months to add 100 pounds to your squat, would you only do the lift once per week? Practicing the lift we want to improve two to four times per week should allow for quicker strength gain.

Research also supports the idea that, even with matched volume, a higher training frequency should lead to superior strength gains (7). For further reading on this, I recommend a very detailed article by Greg Nuckols.

This makes sense, given that strength depends on far more than the amount of muscle mass we have. Neuromuscular efficiency and skill are also vital here.

So, what does this mean? We should do less, but more frequently.

Similar to deciding your training volume for muscle gain, you should start with a weekly volume target and go from there. For example, let's say you want to build up your bench press, and you decide to do 10 weekly sets of bench and its variations. (This is for the sake of keeping your training more fun and preventing overuse injuries.) It can look like this:

Monday - 4 sets of flat barbell bench press

Wednesday - 3 sets of pause bench press

Friday - 3 sets of close-grip bench press

Like hypertrophy training, it's good to start with low to moderate volume, track your progress, and adjust if you have to. For instance, if you're making good strength progress with the above configuration, stick with that until it no longer delivers results. Once you reach that point, consider:

"Do I feel good, and can I add more work for a few more weeks?"

Or:

"Do I feel a bit run down, and should I maybe take a deload week before proceeding?"

The only exception here is the deadlift. I don't typically recommend anyone do it more than once or twice per week. The reason is, deadlifts are pretty taxing, and doing them too often can lead to recovery issues. I recommend a moderate approach here. If your strength stagnates, consider adding a variation like trap bar deadlifts, Romanian deadlifts, or block pulls.

How Many Repetitions You Should Do

Okay, you now have a good idea of how many sets you should do per workout. But how about the number of repetitions? Well, this mostly comes down to your short and long-term goals. Allow me to elaborate:

Research finds that we can build the same amount of muscle mass with different loads, so long as we do enough work and push ourselves hard enough (8). Research also suggests that heavier loads result in greater strength gains, which makes sense. If you bench sets of three reps, you'll likely get stronger than if you bench sets of 12.

So, there we have it. Do heavy sets, build muscle, and get stronger at the same time. It's a win-win. Or is it? Well, as the saying goes, "If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is."

Yes, heavy sets build more strength, and they also build muscle. There is no denying there. But muscle growth relies on doing enough work, which typically means doing enough sets and reps. The problem with heavy lifting is that it's hard work. It taxes your nervous system and puts more stress on your joints and connective tissues. Doing too much of it can lead to injuries and overtraining.

Training with lighter weights is by no means a magic bullet for muscle growth. But it allows you to accumulate enough training volume without exhausting you. It also allows you to perform accessory and isolation exercises with good technique. This includes movements like lateral raises, leg press, and similar.

In general, we should train with 60 to 75 percent of our one-repetition max (1RM) for optimal hypertrophy. This means anywhere from 6 to 30 repetitions per set, depending on the exercise.

For strength, general recommendations are:

- Beginners - 60+ percent of 1RM

- Intermediate and advanced - 80+ percent of 1 RM

Meaning, beginners can get stronger doing anywhere from 5 to 15 repetitions, where more experienced lifters should keep most of their sets at 5 reps or fewer.

Of course, given that you're probably interested in getting stronger and more muscular, I recommend doing 5 to 30 repetitions spread across the exercises you do. For instance, you can do:

- 5 to 8 repetitions on compound movements like squats, deadlifts, and bench press

- 8 to 15 repetitions on assistance exercises like leg press, incline press, and machine rows

- 15-30 repetitions on isolation movements like lateral raises, bicep curls, and tricep extensions

How Many Sets Should I Do: To Sum It Up In 5 Steps

We've covered a lot of ground today, so let's do a quick recap:

1. Follow the guidelines

- 10 to 20 weekly sets; 6 to 30 reps per sets for muscle gain

- 8+ weekly sets; 2-15 reps (depending on experience) for strength

- Train your muscles twice per week, especially as you start doing more sets

- Train lifts two to four times per week if your primary goal is strength gain

2. Start Low

Begin on the lower end of the volume recommendations, track your progress, and gradually increase the amount of work you're doing.

As a rule of thumb, do less work while making progress. That way, you'll have room to add more sets, exercises, and weekly sessions, should your progress stagnate.

3. Pay Attention to Your Recovery

Throughout all of it, pay attention to your recovery between workouts. Do you feel somewhat fresh between sessions? Can you deal with muscle soreness within a day or two? Or do you feel run down, weak, and constantly sore?

Your body will provide feedback and let you know if what you're doing is good or not.

If you can't recover well, reduce the volume for a while, or even take a deload week before getting back to it. On the other hand, if you're recovering well, feeling fresh and strong, and you barely get any soreness, consider adding more work to your weekly program.

4. Keep Your Goals And Nutrition In Mind

The guidelines we've discussed today mostly apply to lifters who are eating at maintenance or slightly over. In other words, these guidelines are great if you're looking to get stronger and build muscle.

Occasionally, you will probably want to take a break from gaining and do a cut. This will help you eliminate some of the fat and take a break from the high-volume training. Speaking of that, you should reduce the amount of work you're doing in a calorie deficit. Your recovery will be impaired, so it's only fair to do less: fewer sets, exercises, and weekly workouts.

Your primary consideration should be to maintain your progress as you lose fat and not overtrain yourself. For more information on it, read this guide.

5. Take The Occasional Break

I'm a big proponent of deload weeks, and I consider them vital for long-term progress. Stress is cumulative, and we need to dissipate it often or risk burning ourselves out. A deload week is a fantastic way to give yourself a reset, melt stress, and get back to the gym stronger and more motivated.

I recommend taking a deload week for every six to eight weeks of serious training. This will vary from person to person, but if you start feeling run down, take it easy for a while.

Mike Israetel also talks about a concept relating to our sensitivity to training. The more work we do, the more we get used to it, and the lesser impact it has on us. Because of that, Mike recommends occasional breaks from high-volume training in favor of low-volume work. This should allow the body to re-sensitize itself to training stress and allow us to make better progress once we increase the amount of work we do.

This makes sense for a couple of reasons. First, we know the repeated bout effect is true (4). The training we do causes less of a disruption because the body adapts and learns how to handle it better. For example, a given workout might generate tons of muscle damage the first time you do it. But do it ten weeks in a row, and you might find it barely causes fatigue anymore.

Second, we need to have a 'volume reset' point every so often. We can't add sets indefinitely because the body has a specific capacity for work and recovery. Taking it easy every once in a while is a good way to get back to the basics and start building again.

Most Importantly Test And Adjust

Science is neat. It teaches us a lot about many things, but here keep this in mind:

It shows averages and does a good job of predicting how a specific thing would impact a large pool of people. But since we work on an individual level, we have to determine how things work for us and adjust based on the feedback we get in the form of progress, general well-being, subjective muscle soreness, and more.

For example, some people do well with higher volumes, where others need a handful of sets to improve. It's your job to make adjustments as you go. So long as you do that, you will learn what works for you.

1. Morán-Navarro R, Pérez CE, Mora-Rodríguez R, de la Cruz-Sánchez E, González-Badillo JJ, Sánchez-Medina L, Pallarés JG. “Time course of recovery following resistance training leading or not to failure.” Eur J Appl Physiol. 2017 Dec;117(12):2387-2399. doi: 10.1007/s00421-017-3725-7. Epub 2017 Sep 30. PMID: 28965198.

2. Krieger JW. “Single vs. multiple sets of resistance exercise for muscle hypertrophy: a meta-analysis.” J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Apr;24(4):1150-9. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181d4d436. PMID: 20300012.

3. Schoenfeld BJ, Ogborn D, Krieger JW. “Dose-response relationship between weekly resistance training volume and increases in muscle mass: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” J Sports Sci. 2017 Jun;35(11):1073-1082. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1210197. Epub 2016 Jul 19. PMID: 27433992.

4. McHugh MP. “Recent advances in the understanding of the repeated bout effect: the protective effect against muscle damage from a single bout of eccentric exercise.” Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003 Apr;13(2):88-97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.02477.x. PMID: 12641640.

5. Vitale KC, Owens R, Hopkins SR, Malhotra A. “Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations.” Int J Sports Med. 2019;40(8):535-543. doi:10.1055/a-0905-3103

6. Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Krieger J. “How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency.” J Sports Sci. 2019 Jun;37(11):1286-1295. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1555906. Epub 2018 Dec 17. PMID: 30558493.

7. Ochi E, Maruo M, Tsuchiya Y, Ishii N, Miura K, Sasaki K. “Higher Training Frequency Is Important for Gaining Muscular Strength Under Volume-Matched Training.” Front Physiol. 2018;9:744. Published 2018 Jul 2. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.00744

8. Schoenfeld, Brad J.; Peterson, Mark D.; Ogborn, Dan; Contreras, Bret; Sonmez, Gul T. “Effects of Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training on Muscle Strength and Hypertrophy in Well-Trained Men,” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: October 2015 - Volume 29 - Issue 10 - p 2954-2963 doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000958

Leave a Reply