For the first three years in the gym, I never bothered to learn the pull-up.

Yes, that’s right. I had been training consistently for about three years and had someone asked me, I couldn’t do a single pull-up to save my life.

Yet, I always felt incredible admiration for the dude who could jump up, grab the bar and bang out a set of ten solid pull-ups like it was nothing.

So I finally decided to get myself together and start progressing.

But… how does one improve upon something they can’t even do? It certainly felt like an impossible task at first.

More...

FREE Download: Get the 2 pull-up progression schemes in a handy PDF file.

First Thing’s First: How to Nail Proper Form Every Single Time

The pull-up looks simple enough - grab a bar and pull yourself up. Well, it seems simple enough, but most people find it very difficult when it’s their turn to do it. It feels awkward, wobbly, impossible even.

I’m sure we can all agree that the pull-up is a challenging movement. Not only does it take a fair bit of strength to perform, but you also need to be mindful of your technique at all times.

Even the smallest changes to your position and bracing can kill the momentum and cut your set short.

So, what I’d like to do is start this guide with a simple checklist of things you should focus on as you grab the bar.

Your 4-Step Pull-Up Checklist

1. Your grip.

Extend your arms up with palms facing out and grab the bar just outside shoulder-width level. Not too wide, not too narrow.

This grip-width puts your shoulders in the best (and safest) possible position for the remainder of the exercise, including the pull, pause, and descent.

Also, make sure to grip the bar firmly by placing your palm over it and enveloping it tightly with your fingers, including your thumbs. You can use a thumbless grip if you want, but I don’t recommend it as I’ve found that it can compromise the length of my set, and it’s been known to cause stabbing elbow pain for some folks.

2. Your core and legs.

As you’re hanging from the bar and before you pull yourself up, straighten your legs, bring your feet together, and engage your core and glutes. You can also engage your calves as well and point your toes downward.

This helps create stability from your core down, and it’s a great way to help you prevent back and forth swinging throughout each repetition. Think of it this way: if your upper body is braced, but your legs hang like jello, you’ll find it much more difficult to stay stable throughout the set.

Plus, keeping your legs stationary helps prevent you from using them to create momentum, which is a great way to improve the quality of each repetition.

3. Your pull initiation: lats, upper back, elbows, and grip.

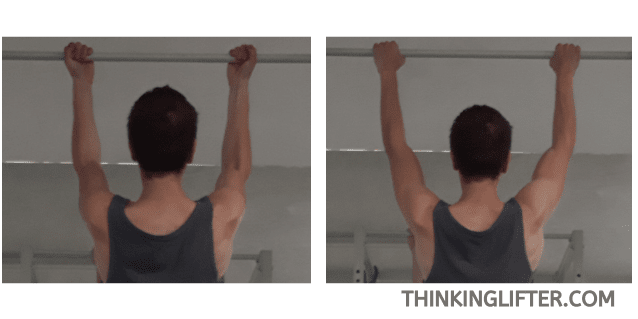

As you hang from the bar in a braced position, bring your shoulder blades back and down (much like you would on a pressing movement).

Then, squeeze hard with both hands and initiate the pull with the idea of bringing your chest out and toward the bar. This is going to help complete and maintain the thoracic extension, engage your lats more effectively, and allow you to maintain shoulder safety (similarly to the bench press).

Also, imagine that you’re pulling through your elbows and your hands serve as hooks to hold your body. This is a neat mental trick that helps create better lat engagement and works for all types of pulling movements.

Another thing you can do is to direct your gaze up toward the bar as you initiate each repetition. This is nothing special, but it may help as it allows you to keep your vision on the target at hand.

4. The top of the repetition and descent.

The goal is to pull yourself up as much as possible, so aim to at least get your chin over the bar. Then, hold the position for a moment and practice a controlled descent - don’t just drop down to the starting position.

First, the controlled descent helps you maintain the pre-established tightness throughout your body, which will be necessary for the next repetition. Second, the eccentric portion (the lowering) of each repetition is just as crucial for muscle growth as the actual pull, so you shouldn’t skimp on it.

Lower yourself to the point where your elbows are entirely straight – or close – but maintain scapular retraction at all times. From there, pull yourself up again.

The Chin-Up Checklist

The technique is mostly the same here. The major difference is that your palms are facing in rather than out.

Note: For the sake of simplicity, I’ll only use the term ‘pull-ups’ from now on, but do remember that most of the information will also apply to the chin-up.

Alright, that’s all fine and dandy, but what if you can’t do a single pull-up? Let’s see:

Pull Up Progression (Even If You Can’t Do a Single Repetition)

This is what I like to call the initial pull-up progression scheme, and it’s intended for complete beginners. So, if you can’t do a single repetition (or you can’t do more than five repetitions in one go), read on.

If you can do over five reps in a single set, skip to the next point for your plan of action.1. Slow Eccentrics (Negatives)

The eccentric contraction is a powerful tool we can use to build strength and muscle, yet so many folks out there don’t think twice about it.

Negatives are particularly beneficial for building enough strength to do a pull-up because you can take advantage of the fact that, no matter how weak you may feel, you can almost certainly lower yourself for at least 2-4 seconds. If you can do that, then you can improve upon it.

The goal is to get yourself to the top position of the pull-up – be it by stepping on something like a chair or a box, or by jumping up – and then fighting gravity as hard as you can. You can do these in a couple of ways:

And, of course, no matter which route you go, remember that progressive overload is imperative here. So what if you can’t lower yourself for longer than 5-7 seconds today? A couple of days from now, you’ll add a few seconds. A few days later, another few seconds. Before you know it, you’ll be able to lower yourself for a solid 30-40 seconds.

I could finally do my first pull up around the time I started holding a negative for about 45-50 seconds.

2. Band-Assisted Pull-Ups

The goal with band-assisted pull-ups is to take away some of the resistance – some of your body weight – and allow you to perform multiple repetitions in a row. Since different bands offer different levels of resistance, you can gradually progress from the most to least resistant as you get stronger.

The only issue is, most gyms don’t have a wide selection of resistance bands, and you may have to buy them yourself. The good news is, you can get a decent set for $30-50 and use them for decades, and not just for learning the pull-up.

You can also use a single band and get different levels of resistance from it, depending on how you loop it. For example, you can start by looping both of your feet – this offers the greatest stretch on the band and thus the most help. Over time, you can eventually begin looping just one foot, then both knees, then one knee. That’s four levels of resistance from a single band.

As a rule of thumb, the more stretched out the band is, the more potential energy it has stored, and the more help you’ll receive from the bottom up.

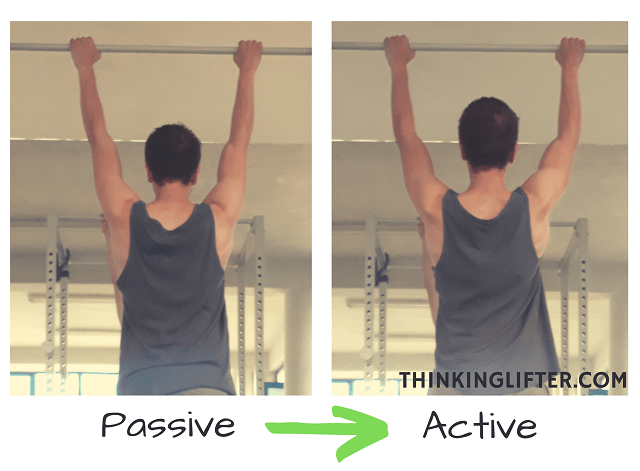

3. Active Dead Hangs

Similarly to how slow negatives build strength and movement proficiency, active dead hangs teach you how to engage your back correctly, keep your shoulders in a safe position, and maintain tightness throughout the set.

To perform these, all you have to do is grab the bar much as you would for the pull-up, but rather than pull yourself up, hang. As you’re hanging, bring your chest out as much as you can while you simultaneously extend your scapulae back and down. Hold the arched position for a moment and loosen up a bit, allowing your traps to sag ever so slightly.

From there, repeat the movement pattern. You can start with multiple sets of three or four reps, making sure to bring your chest out as much as you can before relaxing. Over time, you can work up to sets of eight to ten repetitions each.

4. Inverted Rows

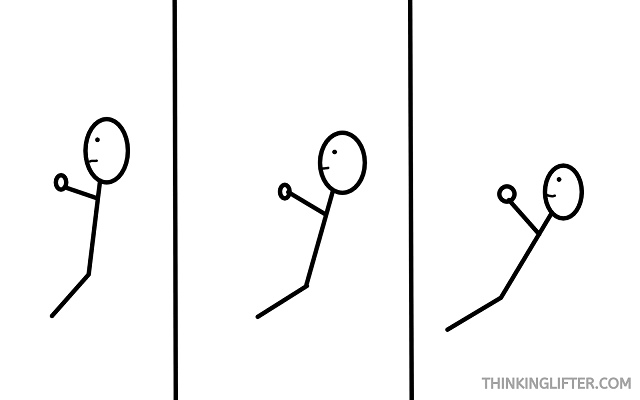

Bodyweight rows are an incredible tool you can use to work your way up to your first pull-up, as they closely mimic the movement pattern and involve the same muscles. The difference is, you’re pulling your body at a different angle, and your feet are in contact with the floor. Depending on the bar height, it takes away some or a lot of the resistance.

A great place to do these is on the smith machine because you can easily adjust the bar height to accommodate your strength level. As a rule of thumb, you should start by setting the bar at roughly chest level. Plant your heels firmly and begin rowing. Aim for three or four sets of eight to ten reps.

As you get stronger, gradually lower the bar, so your body slowly becomes more and more horizontal.

5. Some Fat Loss

This is a no-brainer, but many of us rarely think about it. It’s much easier to work your way up to your first pull-up if there is less weight to pull.

So, if you’ve got some extra fat on your body, losing some of it is going to make the whole process much more straightforward. For example, if you lose 10 pounds of fat and maintain the muscle you have, you’ll find it much easier to do your first pull-up and then work up to 5, 10, and more.

If you’re interested, you can check out my guides on strength training and how to set up your nutrition for fat loss.

So, these are the five tactics you can use to learn the pull-up. I used them years ago, and I’ve had clients and friends do them since then. On their own, each tactic works well. But, together, they make the process much quicker.

The First Pull-Up: Your Action Plan

The more focus you put on these tactics, and the earlier you add them to your workouts, the quicker the progress will be.

Begin by adding 3-4 sets of inverted rows (with the bar adjusted so you can do 8 to 10 repetitions) to one of your workouts – for example, after your primary movements on chest/push day.

Next, add 3-4 sets of band-assisted pull-ups (or chin-ups) and adjust the resistance so you can do at least five repetitions on each set. If you plan on doing those on back/pull day, do them as a first or second exercise while you’re still fresh.

Also, add 2-4 sets of slow negatives to one of your workouts. For example, do your primary moves on leg day (squats, leg press, lunges, etc.) and then do a few sets of slow negatives. You can also do these during a rest day if you have easy access to a pull-up bar.

If you’re interested in getting yourself a home pull-up bar, I recommend checking out the one by IRON AGE.

Finally, add a few sets of active dead hangs in another one of your workouts. Begin by focusing on proper thoracic extension and lat engagement before every worrying about repetition numbers.

The more of these tactics you plan on implementing, the more you should be mindful of your pulling volume. I recommend cutting back on your rowing and deadlifting to a degree, so you don’t end up over-fatiguing your back muscles.

Here’s an example of how you might integrate these tactics on a typical 4-day upper-lower split:

Monday: Upper Body + 3-4 sets of inverted rows (early on, as a first or second pulling exercise)Tuesday: Lower Body + 2-4 sets of slow negatives (after your primary leg exercises)

Wednesday: Off

Thursday: Upper Body + 3-4 sets of band-assisted pull-ups (again, as a first or second pulling exercise)

Friday: Lower Body + 2-4 sets of active dead hangs (after the bulk of your lower body work)

Saturday & Sunday: Off

Alternatively, you can do three of the tactics on rest days (assuming you’re training four days a week) to avoid doing too much volume in your workouts or if you’re pressed for time. I also recommend focusing on a single tactic per day to manage fatigue and keep the quality of repetitions high.

The high frequency and moderate volume are going to help you build up the back strength and movement proficiency to perform the pull-up faster. And if you’re somewhat (or very) overweight, losing some of the excess fluff is going to speed up the process.

With enough consistency, you should be able to do a solid set of three reps within a month. After that, keep repeating until you can do five repetitions in one go.

FREE Download: Get the 2 pull-up progression schemes in a handy PDF file.

Pull Up Progression If You Can Do More Than 5 Repetitions

This progression scheme is for those folks who can do more than five reps in one go. You can use these techniques to work your way up to 10, 20, and even more pull-ups in a single set.

There are a few ways you can go about adding more pull-up reps at this point – some are simpler; others are a bit more complex. For the sake of keeping things actionable and straightforward, I’ll recommend three tactics. And nothing is to say that you can’t use them at the same time.

1. Grease the Groove

Once you’ve built a solid base for your pull-up performance (being able to do between 5 and 15 reps in one go), it’s a good idea to focus on increasing your neuromuscular efficiency. One great (and a bit unconventional) tactic to do that is called greasing the groove. With it, the goal is to focus on frequency and volume instead of intensity and effort.

There are many ways to implement this tactic into your training, and no matter which route you go with, remember to keep effort levels low to moderate and instead focus on doing lots of quality repetitions. This means that you don’t take any sets to failure (or even close) and that you rest plenty between sets. This really shouldn’t feel like your typical style of working out.

That way, you can keep fatigue low, do more total repetitions each week, and build up your prime movers for the particular exercise.

Here are two simple ways to implement this:

a) Do 3-5 sets per day with a frequency of 4-5 times per week.

Always leave at least two repetitions in the tank. For example:

Monday: 4 sets with at least 2 minutes rest in-between (2 reps in the tank)

Tuesday: 5 sets with at least 2 minutes rest in-between (3 reps in the tank)

Wednesday: Off

Thursday: 4 sets with at least 2 minutes rest in-between (2 reps in the tank)

Friday: Off

Saturday: 5 sets with at least 2 minutes rest in-between (3 reps in the tank)

Sunday: Off

b) An autoregulated progression scheme that focuses on a daily repetition goal.

This is by far the simplest and most pleasurable way to go about greasing the groove because it offers a lot of flexibility, and you can go by feel. On days where you feel better, you can do more reps per set. On days where you feel crappy, downregulate, so you maintain a consistent rate of exertion.

For example:

Monday: Repetition goal - 30 total

Tuesday: Off

Wednesday: Repetition goal - 20 total

Thursday: Off

Friday: Repetition goal - 30 total

Saturday & Sunday: Off

Once you’ve established your goals for each workout, do your total repetitions at a pace that allows you to maintain an RPE of no more than 7 or 8. For example, if your goal is 30 total repetitions and you’re feeling particularly energetic, you can go ahead and do five sets of 6 reps. But if you’re not feeling particularly good, you can do them like this:

Set 1: 6 reps

Set 2: 6 reps

Set 3: 5 reps

Set 4: 5 reps

Set 5: 4 reps

Set 6: 4 reps

Or like this:

Set 1: 5 reps

Set 2: 5 reps

Set 3: 5 reps

Set 4: 4 reps

Set 5: 4 reps

Set 6: 4 reps

Set 7: 3 reps

It’s also important to note that you should start with a conservative target and slowly add repetitions to your goal every week. If you can’t do more than five reps in one go, it wouldn’t be a good idea to set a daily goal of 50 repetitions.

And, of course, it’s important to slowly progress your repetition numbers while keeping the level of effort on each set more or less consistent. For example, in the first sample, say that you manage to do a total of 62 repetitions for that week. On week 2, you should ideally be able to add 2-3 reps to your total without exerting more effort into the individual sets.

In our second example, you can simply go ahead by adding one repetition for each day’s goal. Three sessions mean three extra reps.

If you’re interested in getting yourself a home pull-up bar, I recommend checking out the one by IRON AGE.

2. Weighted Slow Eccentrics (Negatives)

Similarly to how negatives can help you do your first pull-up, adding weighted negatives to your program can further improve your pull up progression once you’ve built a solid base.

This is because you can typically overload the eccentric portion of a lift much more than you can the concentric. You can squat down much more weight than you can squat up. You can lower a much heavier barbell than you can row up. The same goes for the pull-up, and this is where weighted eccentrics can help you build more strength or overcome a plateau.

Your best tool here is a plain old weight belt that you put around your waist and can attach plates on.

I recommend starting conservatively by attaching a 10 or 15-pound plate (5-7.5 kilos), so you can get used to the movement and do negatives of at least 5-10 seconds each. If it feels too easy, you can always jump to a 25, 35, or even 45-pound plate.

The goal, as usual, is to do enough volume (which, in this case, would be to rack more seconds on the lowering portion). Much like bodyweight negatives, you can do these in the same two ways:

You can then progress these over the weeks in a couple of ways: doing longer eccentrics and/or adding more weight. For example, you can set a goal of doing four 30-second negatives with a given weight (say, 25 pounds). Once you do that, add 5 pounds and start over.

3. Weighted Pull-Ups

As you get stronger, weighted pull-ups become not only quite useful but also mandatory for you to keep making progress. With that said, I do recommend that you only do bodyweight pull-ups until you work your way up to 12 repetitions in a set.

Now, there are many progression schemes you can use for the weighted pull-up (and, really, any exercise). But I’ve found that more straightforward approaches tend to work better for most folks. I’ve used the below progression scheme on myself and clients, and have found it to work quite well. It’s by no means fancy, but it gets the job done. Here are some notes:

1) This progression scheme has you work the pull-up in the 6 to 10 repetition range.

I’ve found that going lower than that tends to impact technique too much and can often get to the point of ego lifting. You can eventually drop down to the 4-6 rep range, but I’d start with 6-10.

2) You’ll be training the pull-up twice per week.

You can add a third day if you feel like two aren’t enough, but there will be plenty of volume to keep you progressing at a steady pace.

3) We’ll be using a linear model of progression.

It’s simple, it’s easy to comprehend, it’s crystal-clear to track, and it gets the job done.

4) Always leave a couple of reps in the tank.

Training to failure is quite taxing, especially on exercises like the pull-up. If you take your first set to failure, expect to see significant drops in your performance on the remaining sets.If you really want to, take the last set to failure, but stop as soon as you notice that your technique begins to break down.

So, here’s how to start:

The progression:

Once you do three sets of 10 reps with good form, a full range of motion, and an RPE of 7 to 9 (meaning, one to three reps left in the tank), increase the weight and start working up from 6 to 10 again. For example:

Week 1: 3 sets w/ 7.5 kg x 9, 8, 7

Week 2: 3 sets w/ 7.5 kg x 10, 9, 8

Week 3: 3 sets w/ 7.5 kg x 10, 10, 9

Week 4: 3 sets w/ 7.5 kg x 10, 10, 10 (good form, full ROM, no sets taken to failure)

Week 5: 3 sets w/ 10 kg x 7, 6, 6

It’s better to progress more conservatively and always pay full attention to your technique and RPE. Better to take things slowly than to try and increase the weight too quickly, only to find yourself doing crappy repetitions with a weight that is too heavy for you.

The Most Common Pull-Up Mistakes to Avoid

Here are the four most common mistakes I’ve seen folks make with regards to the pull-up:

1. Grip too wide.

This is by far the most common error I see with the pull-up. For some reason, many lifters believe that wider pull-ups equal a wider back. But here’s the thing:

The wider you grip the bar, the more you take your lats out of the movement, and the more you defeat the whole purpose of doing pull-ups in the first place.

This grip-width also puts your shoulders in danger and makes the whole pull more difficult.

Solution:

Grip the bar at about shoulder-width level or slightly wider than that. You’ll involve your lats much more effectively, and you’ll likely notice an instant improvement in your performance. And, to top it all off, it’s a much safer movement pattern.

2. Cutting the range of motion short.

As with most exercises, going through the full range of motion makes each repetition much more difficult. But going through a full range of motion is much more beneficial for strength and muscle development.

Allowing your biceps and lats to stretch and contract on each repetition is going to be much better for you.

Solution:

Leave your ego at the door and make it a point to do each repetition with a full range of motion. This means allowing your elbows to extend fully and always getting your chin over the bar.

If that means doing fewer repetitions, fine – it’s better to do three full repetitions than six half-assed ones.

3. Swinging and using momentum.

It’s well-known that crossfitters use lots of momentum and kipping to perform lots of repetitions in a short amount of time. The problem is, doing pull-ups like that doesn’t train your muscles properly and doesn’t improve your overall pull-up ability. Plus, doing pull-ups in such an uncontrolled fashion increases your risk of injury.

And, let’s be honest here, nobody is going to be impressed by a set of twenty kipping pull-ups. If anything, you might get a few stares and some laughs.

Solution:

Use proper technique and make sure to initiate every repetition from a stable position. If you’re swinging back and forth, make sure to engage your core before each set. It’s better to do a solid set of five pull-ups than twenty half-assed ones.

4. Trying to progress too quickly.

Here’s the thing about progress:

It doesn’t matter if you’re adding more reps or are attaching more weight on yourself unless your form also remains good. The thing is, too many lifters try to progress too quickly and only end up seeing their technique deteriorate for the sake of a few extra repetitions here and there.

Solution:

Follow your progression scheme as outlined. Even if it feels slow and tedious, stick with it because that’s the only reliable way to increase your performance.

If you’re interested in getting yourself a home pull-up bar, I recommend checking out the one by IRON AGE.

4 Things to Remember When Progressing On These Two Movements

Here are four things you need to remember at all times:

1. Changes in Body Weight Will Impact Your Performance

Since the pull-up is a bodyweight exercise, remember that fluctuations can impact your performance – for better or worse. For example, if you’re on a bulk and are gaining weight every week, expect to add repetitions more slowly. You might even feel like you’ve plateaued at times.

On the other hand, it tends to be much easier to add reps on the pull-up during a cut because you’ll be a bit lighter with each passing week.

If possible, weigh yourself in the morning of your pull-up training so that you can more accurately track your performance over the weeks and months.

2. Recovering Between Sets is Non-Negotiable

It’s crucial to give yourself enough time between sets for adequate recovery because that can significantly impact your performance, especially if you’re still in the early stages and can’t do much over five repetitions in one go.

So, if you usually rest between one and two minutes on most sets, give yourself an extra half minute for your pull-ups and see how that impacts your performance. Chances are, you’ll be able to bang out more total repetitions for the workout at a lower RPE.

3. Avoid Taking Any Sets to Failure

Pull-ups have this funny way of coming back to bite you in the ass. For example, if you take your first set to failure (say, by doing ten reps), expect a significant drop in performance on sets 2, 3, 4, etc. This is why it’s so beneficial to do most of your sets at a lower RPE and always leave at least two repetitions in the tank. Think of it this way:

If you hit failure on your first set by doing ten reps, expect to do no more than five on your second set. Set three won’t look any better - you’ll get another five if you’re lucky. And your number of reps is only going to drop further and further from there. And if you’ve set a daily goal of 40 pull-ups, you can see where the problem comes.

Now, if you instead stop at seven repetitions, you’ll be able to keep doing 7s for at least five total sets.

So, rather than it looking like this:

Set 1: 10 reps (failure)

Set 2: 5-6 reps (failure)

Set 3: 4-5 reps (failure)

Set 4 (and onward): 2-4 reps (and dropping)

You can more effectively do your daily volume of 40 reps by keeping the average RPE lower:

Set 1: 7 reps - RPE 7Set 2: 7 reps - RPE 7

Set 3: 7 reps - RPE 7.5-8

Set 4: 7 reps - RPE 8

Set 5: 7 reps - RPE 8.5-9

Set 6: 5 reps - RPE 7

4. Do Not, Under Any Circumstances, Sacrifice Good Form For More Repetitions

We all know this, yet I’ve seen lifters make this mistake over a hundred times. Hell, I’ve been guilty of it myself.

The fact is, we all start a pull-up progression program with our best intentions, “I’ll never allow for my technique to break down. Full ROM all the way!”

But then, as the weeks go by and you’re slowly making progress, you eventually hit the point where progress no longer comes as linearly. That’s just how development goes – it’s linear at first and then slowly tapers off.

But in our efforts to keep progressing with the same speed, we make small compromises with technique – maybe cut the range of motion a bit, use a bit of momentum, etc. I’ve seen this happen with linear progress one too many times (“Gotta hit that 7x5 today!”).

But since it happens on a gradual scale (over the weeks), we rarely notice it. Then, one day, you film one of your pull-up sets and see that your technique has turned to crap.

The solution?

Well, there isn’t any. The best thing you can do is make sure to put a premium on your technique and remind yourself before every single set. You can also film some of your sets and review your technique after each workout - that’s a great way to keep yourself accountable.

So, What’s The Difference Between Pull-Ups and Chin-Ups?

At the start of this guide, I mentioned that I’ll be using the term ‘pull-ups’ for the sake of simplicity, but that most of the things will also apply to the chin-up. So, what’s the difference between the two? And, more importantly, which one should you pick?

Well, folks often use both terms interchangeably, but there are some significant differences between the two variations. The most obvious difference is in hand position – chin-ups have your hands facing you, and pull-ups have your palms facing out. Because of that difference, you can also expect a difference in muscle activation.

For example, the chin-up – particularly when done at shoulder-width level – puts your biceps in mechanical advantage, which means that they contribute a lot more to the movement, and thus get a better growth stimulus. Thanks to that, you’ll also probably find that chin-ups are a bit easier to do than pull-ups – all of the curls are finally paying off.

Pull-ups, however, put your biceps at a mechanical disadvantage, which means that you can’t use them as effectively to pull yourself up. And, when done correctly (with your elbows in line with your torso and hands just outside shoulder-width level), the pull-up puts even more emphasis on your lats and less on your elbow flexors.

In a nutshell, the chin-up is a tad easier and emphasizes your biceps a bit more, where the pull-up is a bit more challenging and trains your back a bit better. But, which should you go for?

You can’t go wrong with either. For example, if you’re a complete beginner and can’t do a single repetition, I recommend starting with the chin-up as it will allow you to progress a bit more quickly. After you’ve built a base, you can introduce pull-ups.

If you’ve already built a solid base, you can cycle the two movements every few weeks or do one variation on workout 1, and the other variation on workout 2.

It’s also a matter of preference – If you prefer one variation over the other, stick with that. Nothing is to say that you must do either of the two.

The Bottom Line on Pull Up Progression

Well, there we are. I hope that you’ve gotten a lot of value from this guide and are ready to apply today’s lessons.

Nothing I’ve shared today is overly-complicated or ‘revolutionary,’ but it works. Simplicity is often all you need to make significant progress in the gym.

With that said, I’ve made all of the progression schemes into handy PDF files for your convenience. You can print them out (or keep them on your phone) for reference while training. To get them, all you have to do is add your email address below:

FREE Download: Get the 2 pull-up progression schemes in a handy PDF file.

Leave a Reply